Doctors will ask about your family history to find out if you have inherited a mutation in one of your hemophilia genes. To do this, they look at your family tree. Doctors can diagnose hemophilia either before a baby is born or afterwards.

Diagnosing hemophilia before birth

If there is hemophilia in the family, some families may want to know if their baby has hemophilia before they are born so they can plan ahead. A pregnant mother can take a test that determines whether her baby is carrying the gene that causes hemophilia while the baby is still in the womb. This is called pre-natal testing.

Doctors can check whether a baby has hemophilia using two types of prenatal tests called amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling (CVS).

Diagnosing hemophilia after birth

Many parents may not be aware of their family hemophilia history and do not ask for a prenatal test. Sometimes, hemophilia is not a part of the family history and you may be the first person to have it. In these cases, doctors diagnose children with hemophilia later in life. A family might notice symptoms common in people with hemophilia, such as more bruising than usual or bleeding into joints and soft tissues with little or no injury.

How do doctors confirm hemophilia diagnosis?

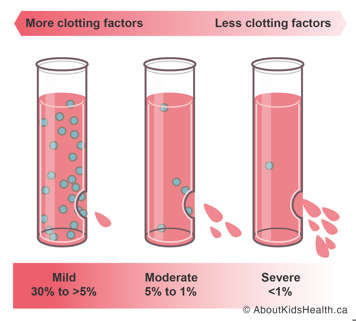

If doctors think you might have hemophilia, they need to run lab tests to confirm the diagnosis. To do this, your doctor takes a sample of your blood to measure the amount of factor in your blood. The test is generally called a factor assay. A special machine in the lab counts the amount of clotting factors that are working inside your blood. By confirming the level of clotting factor in your blood, doctors can find out the severity of your hemophilia. You can have mild, moderate or severe hemophilia. The severity of your hemophilia depends on how much factor your body produces compared to normal levels.

- People with mild hemophilia produce greater than 5% to 30% of the normal amount of factor.

- People with moderate hemophilia produce between 1% and 5% of the normal amount of factor.

- People with severe hemophilia produce less than 1% of normal amounts of factor.

Once a doctor confirms a low factor level, they run special genetic tests. These tests find where the change in the DNA (mutation) has occurred. If the mutation is known, it can give your doctor some information about your hemophilia. For example, some mutations are more severe than others and result in higher risks of complications. Knowing the mutation can also help with future counseling. For instance, if you have a female child, doctors can screen for the mutation to find out if your daughter has a chance of passing the mutation on to her future children. Although most female carriers are not affected with hemophilia symptoms, some may have mild bleeds. A female with mild hemophilia-related bleeds are called symptomatic carriers.

Doctors diagnose your type of hemophilia

There are two main types of hemophilia: hemophilia A and hemophilia B.

Hemophilia A

If you have low or absent levels of clotting factor 8 or have non-functioning factor 8, you have hemophilia A. Because it is the most common form of hemophilia, doctors refer to it as classic or classical hemophilia.

Hemophilia A used to be called “The Royal Disease”. Queen Victoria carried one copy of the hemophilia gene and passed it on to her son, Leopold. As a result, her two daughters Alice and Beatrice were also carriers. However, recent research has found that “The Royal Disease” was in fact due to Hemophilia B. Hemophilia B has been passed through the Royal Family throughout Europe.

Hemophilia B

If you have low or absent levels of clotting factor 9 or have non-functioning factor 9, you have hemophilia B.

Hemophilia B is sometimes called “Christmas Disease”, named after the first person in history to be diagnosed with a deficiency in factor 9. He was a Canadian patient at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto.